Detroit Publishing Co. After the Quake 1906 “The burnt out San Francisco Call newspaper building from Grant Avenue”We have now seen a series of explosions at the stricken Fukushima Dai-ichi plant (Fukushima 1), and it is becoming increasingly clear that containment systems have been breached in at least some units. The pervasive consequences of station blackout began with a hydrogen explosion in unit 1, followed by a much larger explosion in unit 3, two explosions at unit 2 and one at unit 4. Units 1-3 had been operational prior to the earthquake and tsunami, but were automatically shut down with the quake. Units 4-6 had not been operational for some months, but reactors require constant cooling whether or not they are operational. It is likely that we will see all units compromised due to the loss of power that has prevented cooling.

At nearby Fukushima Dai-Ni (Fukushima 2), where there are four units, outside power has apparently been restored and, although three units remain in a state of nuclear emergency. Slightly radioactive steam is being vented in order to reduce the internal pressure from overheating. Similarly, steam venting is being undertaken at the Onagawa plant, where there are an additional three units. Fire was previously reported at Onagawa.

Spent fuel also requires constant cooling in a separate pool, and we are beginning to see problems with its storage at Fukushima 1. The explosion at unit 4 appears to have involved a cooling pool, with water levels dropping. There is considerably more radiation contained in the spent fuel than in the reactor cores, and spent fuel can also suffer a meltdown if cooling cannot be maintained. There are seven spent fuel pools at Fukushima 1, many of them densely packed with some 20 years worth of spent fuel. (All spent fuel world-wide is stored in this way, near the reactors which produce it, as no country has yet developed and implemented a long-term storage solution for waste that will remain radioactive for thousands of years.)

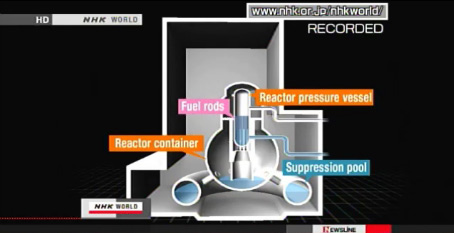

Explosion in reactor no. 3 at Fukushima 1 Monday

The most seriously affected reactor so far is unit 2 at Fukushima 1, where an initial hydrogen explosion was followed by a second explosion in the suppression pool below the reactor. A breach of containment in this unit seems to be the most likely source of the spike in radiation that has recently been noted. Radiation levels of 400 millisieverts per hour were observed at Fukushima, as compared to a normal yearly background radiation level of 3 millisieverts.

Radiation levels have increased to levels harmful to human health, and all but 50 essential workers have been evacuated. The Japanese Prime Minister is has called for evacuation of a 20km exclusion zone. People have been asked to remain indoors and not to bring in laundry drying outside that may now be contaminated. Thousands are being screened for contamination and those with high levels are being showered on site in insulated tents or sent to hospital. Radiation levels are elevated as far away as Tokyo, following a change in wind direction. People are trying to leave the city, but that is becoming more and more difficult as fuel line-ups begin and long distance trains are often not available. Stores are already running out of some supplies as people engage in panic buying. Fear of shortages can easily become a self-fulfilling prophecy under such circumstances. As always, the human reaction to events can provide a major portion of the impact.

In towns and cities fearful citizens stripped supermarket shelves, prompting the government to warn against panic-buying, saying this could hurt the provision of relief supplies to quake-hit areas. But scared Tokyo residents filled outbound trains and rushed to shops to stock up on food, water, face masks and emergency supplies amid heightening fears of radiation headed their way.

The health damage from exposure to radioactive isotopes comes from the energy they release as they decay from unstable forms to stable ones. Each isotope has a specific decay path over a specific timeframe, defined by the half-life of the element. The half-life is the time it takes for quantity of material to be halved, halved again and so on. A short half life indicates a shorter term risk, as the material will release its decay energy over a short time. In contrast, materials with a long half life will be persistent in the environment.

Photo: Kim Kyung-Hoon – Reuters

The health effects will depend on how the particular isotope is taken up in the body, what form the release of its decay energy takes, and what is the residence time of the isotope within the body. Isotopes can decay by releasing alpha, beta or gamma radiation. Alpha radiation is composed of helium nuclei (2 protons and 2 neutrons). These are large and energetic and therefore potentially very damaging), but do not penetrate far. Beta radiation is composed of fast moving electrons, and gamma radiation is composed of photons (light particles). Beta and gamma radiation penetrate to a much greater extent.

The radioactive material of most concern in the initial stages of a nuclear accident is iodine 131, a major fission product which was responsible for the majority of health effects seen so far in the Chernobyl area. Iodine 131 has a half life of only 8 days, so it is of most concern early on. It is taken up by the thyroid gland where it can be retained (especially in young children), greatly raising the risk of thyroid cancer. Taking potassium iodide tablets can protect the thyroid from taking up the radioactive isotope. People in the affected area should be given this option as a preventative measure.

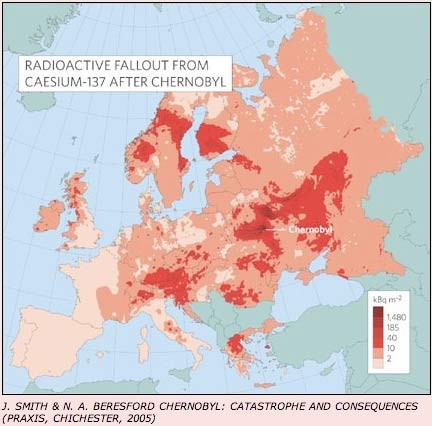

Other isotopes of concern include Caesium 137, with a half life of 30 years, and strontium 90, with a half life of 29 years. Unlike iodine 131, both of these isotopes are persistent in a contaminated area. Caesium 137 is taken up by the body in place of potassium, while strontium 90 is taken up in place of calcium. Caesium accumulates primarily in muscles and organs, while strontium accumulates in bones. The risk is organ damage, leukaemia and bone cancer, depending on the dose. At Chernobyl, caesium 137 appears to have represented a much larger health risk than strontium 90.

Some units at Fukushima ran on MOX fuel (mixed oxide fuel), which would contain a quantity of plutonium 239. Plutonium 239 is an alpha-emitter with a half-life of some 24,000 years. If inhaled or ingested, alpha particles can affect the lungs or digestive system at close range. Explosions at sites where containment is impaired or destroyed are a major risk factor for inhalation of radioactive particles.

It is important to note that the distribution and level of radioactive contamination from the Fukushima disaster is likely to be very much less than at Chernobyl, as boiling water reactors (BWRs) like those at Fukushima do not have the potential for the same failure mode as occurred at the Chernobyl RBMK plant. Chernobyl suffered a nuclear explosion on an abrupt power surge aggravated by a moderator fire.

The Fukushima reactors, where the nuclear reaction had been immediately halted by the lowering of control rods, are instead at risk of meltdown from excess decay heat in the absence of the ability to dissipate that heat. In a full meltdown scenario, the molten core would melt through the pressure vessel and concrete containment, particularly if these have already been compromised by explosive force. The core could melt down into the groundwater, causing steam explosions. Relatively local contamination could eventually be considerable, depending on the final scope of this rapidly developing situation, but I would not expect major international contamination as happened following Chernobyl.

Even within Japan I would not expect widespread gross levels of contamination even under a worst case scenario. Fear of radiation is likely to be widespread and extreme, however, as fear is a phenomenally ‘catching’ emotion, and that can have serious consequences of its own, especially under circumstances where social infrastructure is already overwhelmed. A perception of coverup would add significantly to this fear. It is therefore extremely important for the Japanese authorities to be consistently and completely forthcoming about the situation.

Frightened people are inherently suspicious that they are being kept in the dark to their own detriment, and TEPCO’s former behaviour (falsification of safety records) has aggravated this natural reaction. Japanese Prime Minister Naoto Kan has today criticised the TEPCO utility company for not sharing information after he was not informed of one explosion for an hour after he had already seen it on television.

The risk is that the aftermath of the earthquake and tsunami could be substantially aggravated by the effects of the human herding behaviour we discuss so often here at The Automatic Earth in relation to financial markets (where we are already seeing the effects of fear in Japan).

Those who live closest to Fukushima are the most concerned. “Our feeling is the government is hiding some things, that the information is not fully transparent,” said Hiroko Okazaki, a 60-year-old housewife in Koriyama, the city closest to the crisis-stricken plant. “Even if some experts explain [that it is safe], they might not know the reality on the ground.”

PS: Here is the latest headline from Reuters: Tokyo Electric says may drop water by helicopter onto Daiichi No.4 spent-fuel cooling pond.

This is not going well. This reeks of desperation.

PS 2: The no. 4 reactor at Fukushima 1 is out of control. Fuel rods have been exposed for hours at a time, and they can’t get (enough) water to it -hence the heli dropping “plan”-. What caused the fire in no. 4 is apparently unclear. Also, the suppression chamber at no. 2 appears to be damaged. And the IAEA demands better information sharing from the Japanese government, who in turn blame TEPCO for poor information.