The nature of markets has long been a major focus here at The Automatic Earth. Whereas most commentators treat markets as being driven in some kind of rational fashion by external events, we have concentrated on the irrational endogenous dynamics and the role of sentiment in creating the perceptions that drive positive feedback loops – either virtuous or vicious circles. Sentiment, and therefore perception, can change very abruptly, with far-reaching effects. The events of this past week or so have been a prime example.

The rally of the past two and a half years continued longer than we had anticipated, but on balance of probabilities it is now over, and we are entering the next phase of the credit crunch – the period where a majority begins to appreciate what a credit crunch really means. The first phase, from October 2007 to March 2009, was little more than a mild introduction for many, although even that was enough to push a large number of casualties silently over the edge.

With the dramatic end to the rally (and a loss of over $7.8 trillion in mere days) comes the end of the complacency it engendered. Fear is in the ascendancy once again, and fear is extremely catching. We are already seeing it spread like wildfire and begin to feed upon itself, creating self-fulfilling prophecies. The fundamentals have not changed materially, but the perception of them has, and that is the game changer.

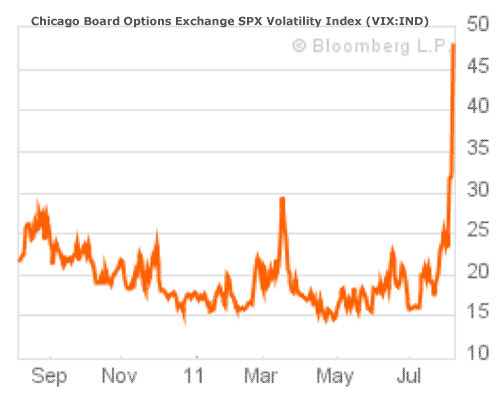

When markets are rising, thanks to optimism and hope, people develop a false sense of predictability, as if events were somehow proceeding as they were meant to, and that they should, by rights, continue to do so. Under such circumstances, market volatility is typically low. In contrast, when markets decline, as fear tightens its grip, that comforting sense of pseudo-certainty evaporates very quickly. Fear breeds extreme volatility as investors try to second guess rapidly unfolding moves, and also each other. The best measure of this volatility is the VIX index.

Initially investors look to buy the dips, on the assumption, born of three decades of expansion, that every decline represents a buying opportunity. Later that assumption will falter, and then fail, but residual optimism takes time to dissipate completely. Every temporary upswing all the way down will rekindle echoes of it. The only relative safety is to be found on the sidelines in cash. While there is money in volatility for some aggressive (and lucky, or well-connected) traders, there will be far more opportunities to lose a fortune than to make one for those who cannot stop playing the game.

Going forward, we can expect more of the stomach-churning market declines we have seen over the past week, but also apparently rocket-fueled, yet short-lived rallies. The sharpest and largest upswings happen in bear markets, interspersed with cascading movements to the downside.

We advise our readers to proceed with great caution and to ignore rationalizations and spurious causation discussed in the mainstream media. In extrapolating past trends forward, failing to anticipate discontinuities, and propagating the smoke-and-mirrors posturing of central authorities desperate to obscure what is happening for as long as possible, they will be arriving at completely incorrect conclusions as to the financial consequences we are facing and what actions we may be able to take in order to protect ourselves. They will also be unhelpfully fanning the flames of fear.

Global commentators have focused recently on the pure political theatre of the rise in the debt ceiling in the US, and subsequently on the downgrade of the US by a single credit-rating agency, but these events do not presage what mainstream opinion has suggested at all. Quite the opposite in fact.

The debt ceiling debate was merely a staged game of brinkmanship, softening up the US population for austerity measures and coming cuts in entitlement programmes targeting the weakest members of society. Imminent default was never a risk. The real risk is the acceleration of the wealth and power grab that has been going on under the guise of quantitative easing for the duration of the rally.

The coverage of the ratings downgrade likewise obscures the real threat. Commentators boldly assert that the US will inevitably have to pay more to borrow, that treasuries are increasingly risky, that the US dollar is doomed and that inflation is an imminent threat. The Automatic Earth has long held diametrically opposed opinions with respect to the next few years, and those are already being vindicated by events.

Our position has long been that the US will benefit from a flight to safety as the least worst option, initially at Europe’s expense. Money will flood from where the fear is to where the fear is not, and one look at bond rates and credit default swap spreads is all it takes to see that the fear is concentrated in Europe, while the US is seen as a safe haven.

When fear rules, small relative differences are enormously amplified, leading eventually to record spreads between debts and debtors perceived to be risky and those perceived not to be, even if that perception is distorted or outright incorrect. As we have said, fear generates self-fulfilling prophecies. As interest rates spiral higher for supposedly risky borrowers, they become less and less able to pay, and default becomes a certainty.

Imposing austerity measures only makes the situation worse, as it forces a contraction that further impairs ability to pay. This is the situation the European periphery finds itself in, and the fear is spreading to include the centre. Today France is in the crosshairs, and even German bond rates are rising.

In contrast rates in the US are falling into negative territory, reflecting the desperation of investors looking for a safe haven and prepared to pay for the privilege. Yields are low because the market is not asking for higher returns, but for a means to preserve capital. The market sets interest rates, not central bankers or governments who only chose a rate to defend, and not ratings agencies without a shred of real credibility left after their performance of recent years.

Interest rates on short term US government debt should stay low throughout the coming period of deleveraging. Short term treasuries represent one of the safest options available, as they are highly liquid, and liquidity will matter more than almost anything else in the depression we are rapidly descending into. Longer term debt may well be a different story, as that has the added risk of having to wait far too long to be repaid, or selling into the secondary market.

Asserting that US treasuries are risky deters ordinary people from seeking the relative safety they offer, even while the insiders take full advantage of it. Similarly, warning people away from US dollars while telling them to hold their nerve in the markets, benefits only those insiders who seek to keep the bubble inflated for long enough to extract their own wealth from a collapsing system.

The US dollar (and other safe haven currencies such as the Swiss franc) is set to benefit, during the period of deleveraging, from the same flight to safety that treasuries will enjoy. It is still the reserve currency, and is likely to stay that way for several years at least. As dollar denominated debt (of which there is more than any other kind worldwide) deflates, demand for dollars, from those seeking to pay down that debt, will push up their value.

The inflation obsession, which central bankers are only too pleased to encourage, also continues to deter people from protecting themselves. Those who are afraid of inflation or hyperinflation will not address the threat of debt or hold the cash that will remain king as the debt bubble bursts and deleveraging aggravates the credit crunch. It is deflation – the collapse of a pyramid of excess claims to underlying real wealth – that we are facing. That is the inevitable result of a bursting bubble.

Widening credit spreads will send the interest rates payable on the debts of ordinary people, companies, banks and lower levels of government through the roof, even as the rate payable on the debts perceived to be safest falls and remains low. At the same time, monetary contraction, credit destruction, spiking unemployment, benefit cuts and skyrocketing bankruptcies will increase the burden that debt represents.

Actual cash will be scarce and few will have access to much of it. Under such circumstances, people will be forced to sell assets for pennies on the dollar to those who still have purchasing power. This is a recipe for extreme wealth concentration, and that, as we are already seeing around the world, leads to increasing social unrest. People need to protect themselves while they still can, but listening to the mainstream media and central authorities is emphatically not the way to do so.

The effect of the US downgrade is ironically far more likely to be felt in Europe than in America. Other triple-A sovereign debtors perceived to be riskier than the US are now at risk of being downgraded, and where fear has already a foothold with respect to sovereign debt default, such moves are likely to aggravate it. Attempts to restore confidence are likely to backfire badly, as existing adverse risk perception merely makes such moves appear desperate, so that they tend to be interpreted as evidence of major problems rather than as reassurance.

Failure is likely to be followed by overtly defensive moves such as the reimposition of capital controls and increasing protectionism, which will only encourage greater fear and greater capital flight. Confidence is ephemeral, and once damaged it can be almost impossible to revive until the underlying imbalance has been resolved, and we are years of deleveraging away from that point.

It is clear the the European Financial Stability Fund, recently increased but still obviously insufficient to cover even the sovereign debt problems already admitted to, cannot solve the rapidly escalating crisis. The scope of this is increasing dramatically as financial contagion spreads to larger states with more intractable debt problems. The European Stability Mechanism, intended to be implemented as a permanent solution in 2013, will never have a chance, as monetary union will long since have been overtaken by events before it can be established.

The European centre has no mandate for further integration, bought, as it would have to be, through the centre agreeing to shoulder far more financial risk than it has done so far. That will likely prove to be politically impossible. The countries of the periphery, caught in a downward spiral of increasingly severe austerity measures and exploding debt, will ultimately resist, perhaps violently, the enormous loss of sovereignty greater integration would involve.

The goodwill necessary to build consensus or render burden-sharing acceptable does not exist, and acrimony is increasing as the situation continues to deteriorate. Larger political accretions become fissile as there is not enough to go around and divisions grounded in history become accentuated anew. This is clearly the risk for Europe.

While rallies are kind to policy makers, casting them in a gloss of apparent competence and effectiveness, declines abruptly strip away the comforting illusion of central control. Policy makers appear increasingly incompetent and out of touch with reality as events unfold far more rapidly than they can be responded to. In reality there is little they can do faced with a bubble blown over at least three decades. Once blown, bubbles always implode.

The demand artificially brought forward during the boom years must be repaid with years of falling demand for almost everything, as difficult as that is to imagine from the top of the pyramid. That is the last thing people are expecting, but it is already underway. Even commodities appear to have topped on speculation going into reverse, and falling demand will accentuate falling prices. The growth dynamic is going into reverse, and with it many of our preconceived and deeply held notions.