Chris Martenson recently posted a rebuttal to the deflationist take on commodities – Commodities Look Set to Rocket Higher. In contrast, our deflationary view here at The Automatic Earth, written at the end of August, is encapsulated in Et tu, Commodities?. To recap, our position is that commodity prices are coming off the top of a major speculative episode and consequently have a very long way to fall.

That is how speculative periods always resolve themselves. We argue, however, that this does not mean commodities will be cheap, even at much lower prices than today, given that the implosion of the wider credit bubble will cause purchasing power to fall faster than price. This means affordability worsening even as prices fall.

To be clear, at TAE we define inflation and deflation as monetary phenomena – respectively an increase or a decrease in the supply of money plus credit relative to available goods and services. Mr Martenson begins his piece with:

Their argument is pretty clear cut: Because inflation is a function of available money plus credit (their definition), and because credit has fallen, deflation is what comes next.

We would point out that, according to our definition, credit contraction does not lead to deflation, it IS deflation by definition. What it leads to is falling prices, virtually across the board.

Mr Martenson points to three conditions which he argues would have to be met for commodity prices to fall, arguing that these are “all just versions of the old supply/demand argument for commodity prices, except that our consideration also includes the important element of the Austrian economic view of demand for money“.

In this view, three things have to be true:

- Demand for commodities has to fall below supply. After all, as long as demand exceeds supply, prices will typically rise.

- Money, including credit that would normally be used to buy commodities, has to shrink. That’s the definition of deflation that we’re analyzing here.

- People’s preference for money has to be greater than their preference for ‘things,’ with commodities being very obvious ‘things.’ That is, faith in money has to be there or people will prefer to store their wealth elsewhere.

Regarding the first condition, Mr Martenson has this to say:

A key component of the deflation argument is that with credit shrinking, demand will drop, leaving excess market supply that resolves with lower commodity prices.”

This does not represent our position, which is based on the powerful impact of bubble psychology, rather than on supply and demand. In contrast, we would argue that for commodity price to fall a long way, and very quickly too, it is not necessary for supply to exceed demand, especially by any significant margin.

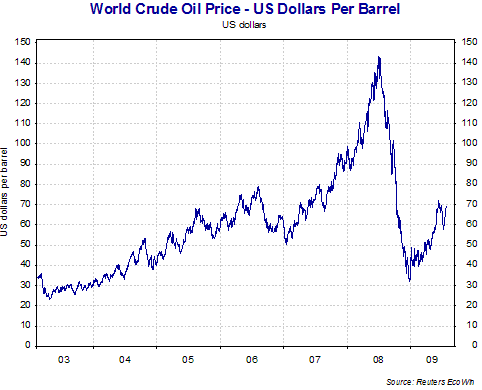

Changes in supply and demand do not typically occur rapidly, but changes in perception certainly do, and it is perception that drives markets. If the fundamentals of supply and demand were responsible for setting prices, we would not see price collapses over a matter of months, yet this is exactly what we saw in 2008.

The dramatic move in 2008 from $147/barrel to under $35/barrel had essentially nothing to do with supply and demand, and everything to do with speculation shifting into reverse, in other words the implosion of a speculative commodity bubble.

The fact that the entire commodity complex showed essentially the same behaviour at the same time, and that financial crisis was becoming acute, strongly suggests that the fundamentals of any particular industry have little to do with prices in the short term, and that financial conditions are a major driver in their own right.

We do expect demand to fall, and for this to have a depressive effect on oil prices further into the future, but we do not expect this to be the primary driver of price collapse in the short term. Our view is that both demand and commodity prices will fall as a direct result of financial crisis, in the form of an acute liquidity crunch, and that prices will do so far more quickly.

The real supply and demand economy responds over a much longer timeframe than financial effects. The ebb and flow of liquidity have been moving disparate markets in synchrony and we expect this to continue. See for instance the common May 2nd top in the S&P, the CRB Index and crude oil.

Speculation going into reverse should account for the majority of the downward price move we expect to see, which we anticipate will (temporarily) take prices below the 2008/2009 bottom. Since then, prices have once again been bid up on fear of shortages, as they were into the 2008 top. This is very typical for commodities.

Commodity bubbles form on the perception of imminent scarcity, which leads to additional money flooding into a sector on the grounds that future prices ‘must rise’, and that there are therefore profits to be made by betting on a rise. This response is accentuated where purchasing power is plentiful and leverage readily available, as during a period of credit expansion. The perception of near-term scarcity can then become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Acute fear of shortages gets ahead of itself, driving prices to unrealistic heights in a classic Ponzi structure that will collapse once the Greatest Fool (or most aggressive speculator) has committed himself, and there is no one left to drive the trend further in that direction. The speculative premium disappears, and then opposite dynamic asserts itself – speculation that prices will now fall, which becomes another self-fulfilling prophecy.

Speculative reversals are thus followed by a temporary undershoot, as we saw in 2008. Prices fall to well below where the fundamentals would place them – in the case of commodities perhaps to the cost of the lowest price producer.

Mr Martenson says:

If it costs $70 – $80 to produce a new barrel of oil, the price cannot fall much below that for very long.

Production costs are very likely to fall in a deflationary environment, albeit not nearly as quickly as oil prices, meaning that many suppliers would be squeezed. The cost of the lowest prices producer could end up considerably below where it is today. Prices could temporarily undershoot even this level.

We have seen in North American natural gas markets, in the context of shale gas, that production can temporarily be maintained at unprofitable levels. We do not expect a downward price spike to extremely low levels to be maintained for long, however, because production costs falling more slowly than price will eventually drive producers out of the market, reducing the (temporary) excess of supply.

Approaching scarcity leads not to a one way trip to the moon in price terms, but to an exaggerated boom and bust dynamic, which we have seen in force since 2006. The fundamentals interact with perception, and the inevitable resulting herding behaviour, in complex, yet probabilistically predictable, ways. Movements in both directions can be large and rapid. Volatility, in response to fear and uncertainty, is the name of the game.

Markets are creatures of positive feedback, and commodities are no exception. It is not enough to understand the fundamentals. One must also understand how those fundamentals will interact with human nature at a collective level. As in quantum physics, the observer and the system are not independent. The view of prices as a function purely of supply and demand rests on the notions that markets are rational, efficient and omniscient, and that human effects are an irrelevant external factor.

We maintain that this view is a completely inaccurate description of reality. Human actions, particularly the collective actions of herding behaviour, cannot be assumed away – they must be viewed as an inherent, and indeed vital, component of the system. Human beings chase momentum, often in the absence of any real information at all. They jump en masse on to passing bandwagons on the assumption that someone must know what they are doing.

We regard markets as fundamentally irrational and driven by emotionally-grounded perception, not by reality. They exhibit an eternal tug-of-war between collective greed and fear that expresses itself in fractal patterns. This lends itself to technical analysis (based on Elliottwaves), but not of the kind mentioned by Mr Martenson in his article. Elliottwaves identify and rank different unfolding possibilities for market action. There are always many possibilities as fractals unfold at all degrees of trend simultaneously.

The highest ranked option will be the one that satisfies the greatest number of guidelines while violating no rules, but it is not always the highest probability option that plays out. What Elliottwave analysis does is to indicate higher and lower probability time periods for trend changes, and boundaries for interpreting subsequent price action in the context of different possbilities, providing advance warning of potentially significant moves. In conjunction with contrarian sentiment indicators, it is a powerful, if inherently probabilistic, tool.

Continuing on the supply and demand theme, Mr Martenson comments on the apparently insatiable demand of India and China:

What’s new in this story today is the emergence of a couple of new economic powerhouses with billions of citizens as new participants at the resource table….We’re seeing exactly what you would expect from a major economy expanding like crazy: a rapidly growing, or, shall we say, exponentially increasing hunger for natural resources….Perhaps a slump in the Western economies will suddenly flood the world with enough resources to cause a commodity crash, but perhaps not….

….So on the first deflationist point that supply of commodities will soon greatly exceed demand, I have to conclude that until and unless we see China’s and India’s economies fall off a cliff, the impact of bringing an additional 2.5 billion consumers to the global buffet of natural resources will provide ample pressure to prevent a sustained crash in prices. Perhaps we’ll experience a short-term correction, especially if the Fed is stingy with its still-unannounced QE III program, but a long-term crash seems highly unlikely.

We have said for some time that we do not expect the Fed to provide a QE3. Even if it were to attempt to do so, we are of the opinion that it would be a miserable failure. The previous rounds of quantitative easing occurred against the backdrop of a supportive rally, and rallies are kind to central authorities by making their actions appear effective. Rallies unfold on a temporary resurgence of optimism, which leads people to extend credence to their leadership.

This suspension of disbelief allows interventions to achieve apparent traction. Once this supportive psychological milieu gives way, however, and the larger down-trend is back in force, which it has been since May 2nd, optimism rapidly dissipates and disbelief reasserts itself. The actions of central authorities under such adverse conditions are very likely to appear incompetent and useless. Kicking the can further down the road under such circumstances will be exceptionally difficult.

Exponential growth, particularly in the form of a dramatic parabolic rise, as we have seen in India and China, is the hallmark of a bubble living on borrowed time. Exponential growth curves end in collapse, and those in India and China will be no exception.

In other words, it is not just western economies that are poised to experience a sharp reversal of fortunes, but the rapidly growing BRIC countries as well. They too have lived through massive credit expansions, with concommitant build up of unpayable debt, and like western countries, their bad debts are set to messily implode in credit crunch and demand crash.

They have focused on building an export economy during their expansion phase, and have benefited from a global consumption boom, but that is coming to an end. Much of the export capacity, built on bad debt, will prove to have been wasted capital as consumption collapse, and with it export markets.

As empires in the ascendancy, the difficulties of India and China are likely to be less intense and more transitory than the old imperial centres moving into decline. For this reason, their domestic demand is likely to recover far more quickly, although the death of their export markets will be an enduring factor that could yet take considerable time to overcome.

If by the time Indian and Chinese domestic demand begins to recover enough to overcome the loss of export-driven demand, global energy supply has been squeezed by low prices, we could expect a major price spike in the next few years on the continuation of the exaggerated boom and bust cycle continues. A potential future resource grab would accentuate this considerably. Prices for commodities such as oil could therefore bottom relatively early in this depression.

We at TAE are not failing to recognize in our arguments either resource limits or recent demand history in the BRIC countries. However, we are firmly of the opinion that it is primarily money rather than natural resources that we and others will find ourselves acutely short of over the next few years. Beyond that, we can expect resource limits to reassert themselves. In volatile times, different factors can become limiting at different times, and relative values can change almost overnight. The key is to anticipate these moves, which is far more challenging than merely extrapolating current trends into the future, as many analysts commonly do.

The second condition Mr Martenson cites is that money, including credit that would normally be used to buy commodities, has to shrink. His objection is that:

This explanation is especially problematic for me when it is used in an overly broad way by lumping all credit market debt into a single spot and then saying, “There. Look. It’s fallen. Credit is down, and that’s deflationary.”….(Hey, credit has to be paid back at some point, right? So it’s roughly neutral over the long haul.)

As I pointed out previously, credit contraction is not deflationary, it IS deflation by definition. We not only regard this as inevitable, we would argue that it is already well underway. Credit began to contract in 2008 for the first time since WWII. Although it has bounced back to some extent with the rally from March 2009, it has not regained its peak. Now that the larger downward trend has resumed, we can expect credit contraction to reflect this, following a time lag for the contraction to appear in the data.

To argue that credit is neutral, since it has to be paid back at some point, is to miss an enormous impact between the begging of a credit expansion and the end of its aftermath. Credit has the effect of bringing demand forward and then crashing it thereafter. The effect may be neutral if one takes a sufficiently long term view, but that view would have to cover several decades of tremendous boom and bust. Averaging that out over such a period of time would be to miss the largest factor influencing commodity prices for a century, or indeed perhaps in history, and that seems highly counter-productive to the effort of understanding what is happening and why, and how it will play out from here.

The collapse of the Ponzi credit expansion of the last thirty years will crash the effective money supply, given that credit represents the vast majority of that money supply today. Credit represents excess claims to underlying real wealth. During the bubble expansion phase, the increase in claims to wealth greatly outstrips any growth in real wealth. The flip side of credit expansion is debt, hence during a credit expansion, debt becomes less and less well collateralized, and the real economy more and more hollowed out as a result.

The blinding optimism characteristic of expansion keeps people from noting this fact until it is far too late to prevent a debt implosion that will proceed at least until the small amount of remaining debt is acceptably collateralized to the few remaining creditors.

The excess claims that credit represents will be largely eliminated under this scenario. Confidence and liquidity are equivalent. When confidence evaporates, as it does on the recognition of of an unpayable debt predicament, liquidity will shrink proportionately. This cannot help but reduce purchasing power. In fact, ‘reduce’ is a considerable understatement from the perspective of the vast majority of people.

The depression conditions that result from the bursting of a large bubble can virtually eliminate purchasing power for many, or perhaps most. Since the aftermath of a bubble is roughly proportionate to the excesses that preceded it, and this has been the largest bubble in human history, we can expect an extremely severe depression to follow.

Mr Martenson distinguishes between the effect of credit expansion and contraction on financial assets versus the effect on the consumer price index (CPI), suggesting that the two are independent, and that effects in the financial sector have little effect on the real economy:

The trouble I have with this view is that not all credit has the same impact on demand. Some credit leads to demand that directly impacts the CPI (inflation), and some does not. When we are talking about inflation, what most people care about is the price of things they use or consume (cars, food, gasoline, health care, houses, etc.), rather than financial instruments or paper assets (stocks, bonds, derivatives, etc.)….Whether credit-default swaps (CDS), traded within and among the shadowy world of purely financially motivated entities, are trending up or down in price has almost zero impact on the price of molybdenum or corn.

It is difficult to imagine how the disappearance of access to credit, combined increased debt burden on spiking interest rates, skyrocketing unemployment, falling (and highly insecure) incomes, loss of pensions and other entitlements, loss of investment value as asset prices collapse, and loss of savings to a systemic banking crisis, all of which are typical of deflationary episodes, could possibly fail to have a dramatic impact on people’s collective purchasing power.

The tremendous potential impact on purchasing power in turn cannot help but impact upon the ability of people to convert their wants into what they can actually afford. It is not that people will no longer want commodities, or many other goods and services, but that they will not be able to afford them in anything like the previous quantity. Demand is not what one wants, but what one is ready, willing and able to pay for. For a time, supply will be geared to the previous level of demand, leaving a substantial surplus that should weigh on prices for a significant period of time.

The odds of people being able to pay what they once could for commodities under such circumstances are effectively nil. It is as if we were playing a giant game of musical chairs, where there is only one chair for every hundred people playing the game. When the music stops, most will be out of the ‘game’ after a short but chaotic wealth grab.

If we see a resurgence of demand in BRIC countries sooner rather than later, perhaps accompanied by future price spikes and resources grabs, the firming up of price support at that time would almost certainly price a large number of people in depression-gripped western countries out of the commodity market entirely, since their purchasing power would not have recovered. This would be a recipe for significant socioeconomic unrest in a large part of the world.

Mr Martenson asserts that:

“There’s been $3 trillion of new credit created in the consumptive portion of the economy since the start of the financial crisis in 2008, and it’s almost entirely thanks to government borrowing. Not too shabby.”

We would argue that demand supported by government borrowing is entirely artificial, amounting to a further episode of bringing demand forward at the expense of the future. This cannot be realistically argued to be a positive effect on the global economy going forward, as it will result in a further paucity of future demand, and consequent downward price pressure. The future pain in store for suppliers, and the probability of a consequent future supply squeeze, are amplified by this action.

Mr Martenson’s third condition involves the demand for money versus the demand for tangible stores of value. He suggests that we should bear in mind the shift from perceived value of paper assets towards commodities and other real assets. While we would agree that over the long term such a shift will indeed take place, our view is that we are about to see a sharp reversal of this trend in the short term. Cash is king in a deflation.

In our view, we are going to see a rapid and substantial shift towards a desire to maintain liquidity, on the grounds that liquidity represents uncommitted choices, and that people will be anxious to maintain their freedom of action to respond to massive uncertainty. This is likely to last into the medium term (ie probably a number of years). It is absolutely vital to anticipate this type of trend change. Extrapolating past trends forward is simply not good enough.

Mr Martenson points to measures of monetary expansion as evidence that deflation is not in fact occurring:

There is absolutely nothing deflationary in the M2 chart. It is exactly what we would expect to see from a culture that placed a man at the monetary helm on the basis of his promise (Jackson Hole, 2002) to run the printing presses if deflation came knocking.

We would argue that expansion of narrow measures of money are largely irrelevant, since they are dwarfed by credit contraction over the same period, and deflation is defined as contraction in the supply of money plus credit. Also,it cannot be ignored that the velocity of money is plummeting, which is characteristic of the developing economic seizure we anticipate in a depression. This will resemble Dante’s Ninth Circle of Hell – a frozen lake where nothing moves.

Gustave Doré Satan trapped in the frozen lake Cocytus in the Ninth Circle of Hell 1857

Illustration for Dante Alighieri’s Commedia [Divina]: Inferno